|

|

|

|

|

Stress-free Training Enhances Surgical Skill

New Report: Surgical Skills Easily Acquired When Learning is a Hobby

HOUSTON, Feb. 2019 – University of Houston and Houston Methodist Hospital researchers are reporting in Scientific Reports ((link)) that the best way to train surgeons is to remove the stress of residency programs and make surgery a hobby. Under relaxed conditions outside a formal educational setting, 15 first-year medical students, who aspired one day to become surgeons, mastered microsurgical suturing and cutting skills in as little as five hour-long sessions

“It appears that by removing external stress factors associated with the notoriously competitive and harsh lifestyle of surgery residencies, stress levels during inanimate surgical training plummet,” said Ioannis Pavlidis, Eckhard Pfeiffer Professor and director of the Computational Physiology Lab at UH. “In five short sessions these students, approaching surgery for fun or as a hobby, had remarkable progress achieving dexterity levels similar to seasoned surgeons, at least in these drills.” His partners on the project, Anthony Echo and Dmitry Zavlin, surgeons at Houston Methodist Institute for Reconstructive Surgery, gave brief instructions to the students at the beginning of the program.

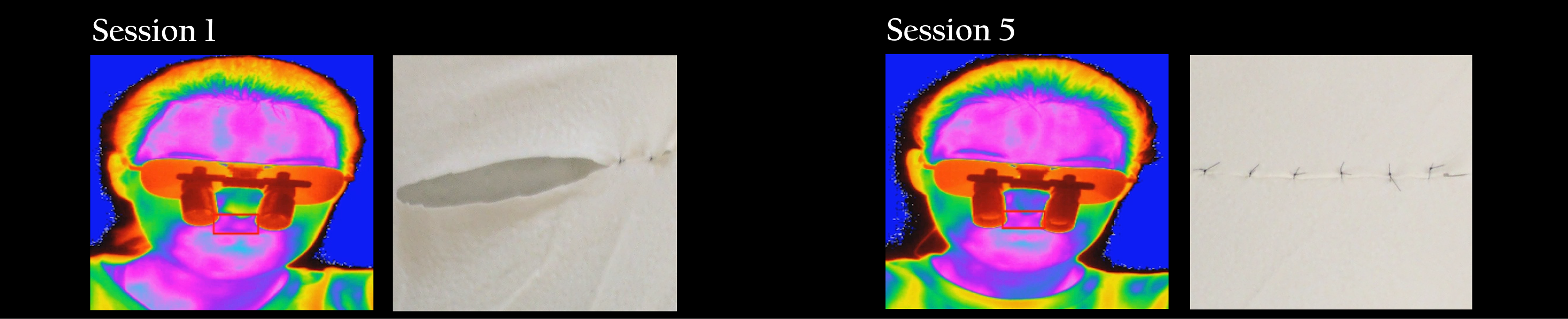

Once the students began cutting and suturing at their mobile microsurgical simulators, Pavlidis and team tracked their stress levels by measuring sweat responses near the nose via thermal imaging. The students’ performance in the surgical drills was scored by two experts, based on video recordings.

In previous work Pavlidis and Houston Methodist Hospital researchers found that surgical residents exhibited high stress levels during their formal training in surgical simulators. These high stress levels precipitated “fight or flight” responses, resulting in fast, mindless actions leading to errors and creation of a vicious cycle during the surgical drills.

In the present follow-up work, Pavlidis, Echo and Zavlin chose trainees outside the surgical establishment, without pressures and stakes, to examine what happens when environmental stress is neutralized and only stress associated with the challenging nature of the surgical drills is present.

“We removed stressful environmental factors, leaving only the inherent challenge of the surgical tasks, and discovered the physiologically-measured distress in the form of sympathetic arousal was moderate and unchanged throughout the five training sessions,” said Pavlidis. In contrast, Pavlidis reported in the previous study high stress levels in surgical residents and slow learning processes, where five training sessions brought no skill improvement. The main factor that sets the two studies apart is the educational context and stress associated with it.

In this study, where young surgery enthusiasts took up surgical training without the impact of environmental anxiety, skills were quickly acquired. Then once a skill like suturing is acquired, it won’t be forgotten, much like riding a bike.

“If you acquire a dexterous skill when you are not super stressed, you will acquire it better and faster, because `fight or flight’ responses are not there to mess things up,” said Echo. “And once you have it, the skill won’t leave you. Like a bike, once you learn to bike, you bike,” Pavlidis added.

Future surgery residents with the skill acquired at a more opportune time would be able to focus on more advanced experiences inside the operating room. “Similar paradigms may apply to other artisan professions, upending training doctrines held sacred for generations,” said Pavlidis.

|

|

|

Stressed Surgical Residents Underperform in Formal Surgical Training |

|

|

|

Video 1: Stressful Conditions Prompt Fast Actions, Impeding Dexterous Skill Acquisition in Surgery

|

|

|

|

Medical Students Excel In Surgical Training When Taken As A Hobby |

|

|

|

Video 2: Absence of Stressful Conditions Accelerates Dexterous Skill Acquisition in Surgery

|

|

|

INVESTIGATORS: Ioannis Pavlidis - Dmitry Zavlin - Anthony Echo

INVESTIGATORS: Ioannis Pavlidis - Dmitry Zavlin - Anthony Echo

FUNDING: The work was supported by a grant from the Plastic Surgery Foundation (consortium agreement no. 001).

RESEARCH ASSISTANTS: Amanveer Wesley - Ashik Khatri - George Panagopoulos

INSTITUTIONS: Computational Physiology Laboratory, University of Houston, Texas, USA

PAPER: To read the paper, go to: Pavlidis et al., Sci. Rep. 2019

DATA: To access the dataset associated with the paper go to: https://osf.io/9he58/

DATA: To access the dataset associated with the paper go to: https://osf.io/9he58/

BLOG: To read the story behind this research, access the blog of Dr. Pavlidis at: WordPress